5 Must-Know AANHPI Women Who Shaped Democracy

Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) women have always been an integral part of the voting rights movement. From opposing sexist and racist legislation to expanding the freedom to vote, the following five women are just a few of the many icons you should know about.

Patsy Mink

Patsy Mink

Patsy Mink was a third-generation Japanese-American attorney and politician born and raised in Maui. After graduating as class president and valedictorian of her high school, she enrolled in the University of Nebraska, where she worked to eliminate segregationist policies. She then earned a degree in law, but was blocked from taking the Hawaiian bar exam because her recent marriage invalidated her Hawaiian territorial residency.

Mink challenged this barrier and won the right to take the bar, but after passing, she had trouble finding a job because of her status as a married mother. Inspired to change the sexist policies that held her back, she ran for the territorial House of Representatives in 1956. She won, becoming the first Japanese-American woman to serve in both the territorial House and, two years later, the territorial Senate.

After Hawaii achieved statehood, Mink became the first woman of color to win a seat in the House of Representatives. During her time in Congress, she promoted childcare, education, immigration reform, social welfare, and anti-discrimination bills such as Title IX of the Higher Education Act, later renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act. She also passed the Women's Educational Equity Act, which aimed to increase gender equity in schools and provide increased education and job opportunities for women.

In 1972, she became the first East-Asian woman to seek the Democratic Presidential nomination, running under an anti-war stance. In 1990 she was once more elected to the House of Representatives, where she worked until her death in 2002.

Tye Leung Schulze

Tye Leung Schulze

Tye Leung Schulze was born in San Francisco in 1887. In her teens, she became a translator for her local mission home, where she assisted in the rescue of human trafficking survivors. At 23, she became the first Chinese-American to pass the civil service examinations, which allowed her to work as an interpreter on Angel Island.⠀

⠀

In May 1912, Leung Schulze became the first Chinese woman to vote in a presidential primary election. Yet prejudice still cast a pall over her life; the very next year, she was fired from her job at Angel Island because of her marriage to Charles Schulze, a white immigration officer. The marriage was deemed to violate anti-miscegenation laws.⠀

⠀

Leung Schulze continued to work, providing interpretation and social services to San Francisco's Chinatown residents. She had four children and was linked to women's rights advocacy until her death in 1972.⠀

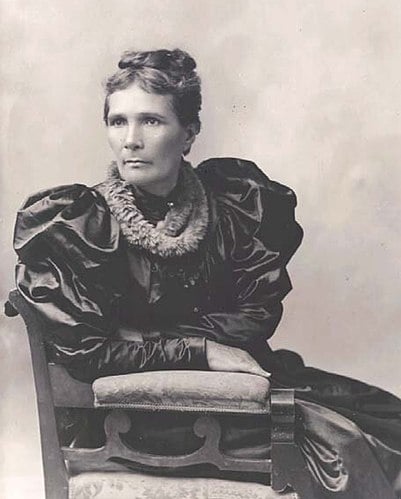

Emma Kaʻilikapuolono/Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina

Emma Kaʻilikapuolono/Kaili Metcalf Beckley

Nakuina

Emma Kaʻilikapuolono/Kaili Beckley Nakuina was a judge and cultural writer born in Hawaii's Manoa Valley prior to the US overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Her father was a New York sugar planter and her mother was a descendant of the aliʻi (hereditary nobility) of Oahu.

She was extensively educated as a young woman, and at one point, she was ordered by Hawaiian King Kamehameha IV to study traditional water rights and customs. Nakuina served as a lady in waiting to Queen Kapiʻolani before being appointed to the role of curator to the Hawaiian National Museum and Government Library. In this role, Nakuina established herself as an expert on Hawaiian folklore and history. Because of her knowledge of water rights, she was later appointed commissioner of private ways and water rights. For taking this role, she is often regarded as Hawaii's first female judge; fittingly, she was nicknamed "judge of the water court."

When the Hawaiian Queen Lili’uokalani was overthrown in 1893, Hawaiian women lost the right to vote. In response, Nakuina co-created the National Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai’i, which used publications, public speaking opportunities, and social functions to advocate for women's suffrage.

Nakuina also worked to preserve Hawaii's culture and history as colonization threatened to eradicate it. Her book "Hawaii, Its People, Their Legends" translated several Hawaiian stories into English so that non-Hawaiians can better understand her homeland's culture.

Nakuina passed in 1929 at the age of 82.

Dr. Sayu Bhojwani

Dr. Sayu Bhojwani

Dr. Sayu Bhojwani was born in India and spent various periods of her childhood in Belize and British Honduras. In 1980, she moved to the US for college, with the initial intention of teaching English. ⠀

⠀

When the US government denied her assistance in obtaining a green card, she turned her focus from education to work with the Asia Society. In 1996 she founded South Asian Youth Action to support teenagers with South Asian ancestry.⠀

⠀

In 2002, Dr. Bhojwani was appointed as New York's first Commissioner of Immigrant Affairs; in this role, she served and protected millions of people. In 2010, she founded the nonprofit New American Leaders, which recruits people of immigrant heritage to run for national office, and in 2020 she founded Women's Democracy Lab, which supports women of color in elected office. ⠀

⠀

Today, she continues her work as an author, speaker, democracy futurist, and immigrant rights advocate.

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee was a Chinese American activist and suffragist. She is also the first Chinese woman in the US to earn a doctorate in economics. ⠀

⠀

Lee was born on October 7, 1897, and spent her early childhood in China. Her father, Dr. Lee Towe, was a missionary pastor and moved to the US when Lee was four. When Lee was nine, she received an academic scholarship that allowed the family to relocate to the US to be with her father. ⠀

⠀

At sixteen years old she was admitted to Barnard College and led a women’s suffrage parade in New York. The parade drew in ten thousand attendees. Lee was deeply devoted to her studies and wrote feminist essays for The Chinese Students’ Monthly that emphasized the importance of extending voting rights and equal opportunities to women. ⠀

⠀

She did this in spite of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prevented Chinese immigrants from attaining citizenship and voting. Even when the 19th amendment passed, Chinese women and many other women of color were not allowed to vote. In 1916, Lee gave a speech at the Women’s Political Union’s Suffrage Shop encouraging the education and civic participation of Chinese women of all ages. ⠀

It took twenty-five years for women like Lee to be granted the right to vote with the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. After graduating from Barnard College, Lee went on to get receive a master’s degree in educational administration from Columbia Teacher’s College. Later, Lee pursued a Ph.D. from Columbia University. She became the first Chinese woman to graduate with a Ph.D. in economics. ⠀

After her father’s death, Lee took over his role as head of the Baptist mission in Chinatown. She also opened a community center, the Chinese Christian Center. This center was meant to empower the Chinese community by offering a health clinic, English classes, and a Kindergarten. ⠀

⠀

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee’s activism ensured many other women had the ability to vote. She also devoted her life to service and advocacy for her community until her death in 1966. ⠀

The Latest from the League

We're excited to highlight some of the accomplishments, advice, and experiences of our fellow Leaguers who identify as members of the AAPI community. As you'll see, each of these five people has had an enormous, positive impact on the League, our democracy, and the people around them.

The League joined a letter drafted on behalf of the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA), the Democracy Initiative, and more than 150 undersigned organizations to denounce the continued increase in racist attacks and discrimination against the Asian American community.

The Native women of Haudenosaunee played a vital role in the women’s suffrage movement. Their way of living — equal participation in their government and societal roles — heavily influenced the movement’s early stages.

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate to support our work

to empower voters and defend democracy.