Voting Rights Heroes in the Disability Community

Happy Disability Voting Rights Week!

Per the American Association of People with Disabilities, there are currently 38 million people with disabilities who are eligible to vote.

And our history is replete with people with disabilities who paved the way for a stronger, more representative democracy — like Judy Heumann, Sojourner Truth, Senator Tammy Duckworth, Claudia Gordan, Harriet Tubman, Joyce Ardell Jackson, and Vilissa Thompson, to name a few.

Yet we also know that anti-voter laws and regulations disproportionately impact people with disabilities, and the fight to make the vote more accessible is ongoing.

In this blog, we’ll highlight some of our favorite voting rights activists who were also women with disabilities. Then, we’ll examine how ability and voting rights intersect today.

Voting Rights Icons in the Disabled Community

Rosa May Billinghurst and fellow suffragists

Rosa May Billinghurst

Born in Lewisham, England, in 1875, Billinghurst contracted polio during childhood, which led her to use a tricycle wheelchair for the rest of her life. In addition to teaching Sunday school and engaging in social work, she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (she later started their Greenwich chapter). Within the organization, she was known for using her tricycle during protests to ram into police officers.

In addition to the hardships faced by her fellow protestors, Billinghurst faced discrimination and violence around her mobility. During the famous Black Friday suffragist protest in 1910, Billinghurst was forcibly thrown from her tricycle by law enforcement, who then took the machine apart, leaving her stranded in the crowd. This was not the last time police destroyed her tricycle, as they’d do so again at a protest in 1914.

In 1911, Billinghurst was arrested for breaking windows during another suffragist protest. In jail, despite having irons placed on both legs, she often drove her tricycle around the prison yard “at exercise time...painted in colors, with a placard, Votes for Women, on the back of it.”

Billinghurst continued to promote women’s equality and the right to vote through speaking engagements, public protests, hunger strikes, boycotts, and support of various women’s organizations. In her lifetime, she saw women granted the right to vote.

“The government may further maim my crippled body...they may even kill me in the process...but they cannot take away my freedom or spirit or my determination to fight this good fight to the end.”

Fannie Lou Hamer with women, including activist Heather Booth

Fannie Lou Hamer

Civil rights icon Fannie Lou Hamer was born in 1917 in Mississippi. While she’s one of the more known figures in the civil and voting rights movements, her identity as a woman with a disability is often buried.

Like Billinghurst, Hamer suffered a bout of polio as a child that is typically cited as the source of her permanent limp. The injury worsened after an incident of police brutality in 1963 when Hamer was beaten by police after attending a voter registration program. In addition to worsening her limp, the arrest left her with permanent eye and kidney damage.

Hamer made clear that her disabilities were an important part of her activism. As academic Keisha N. Blain says, “[s]he spoke about all the ailments and she spoke about them over and over again, so that even if you didn’t see it — if you encountered her and didn’t necessarily notice the limp — she would tell you, because that was part of who she was.”

Notably, she spoke about her injuries (and the attack that caused them) in her testimony before the 1964 Democratic National Convention – testimony that was later rebroadcast during primetime news and made it impossible for the nation to ignore the reality of racist voter suppression. Less than a year later, the Voting Rights Act was signed into law.

In addition to public speaking, Hamer registered voters, co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the National Women’s Political Caucus, established farm cooperatives with the National Council of Negro Women, advocated for federal funding for Head Start, and even ran for Congress.

“When I liberate others, I liberate myself.”

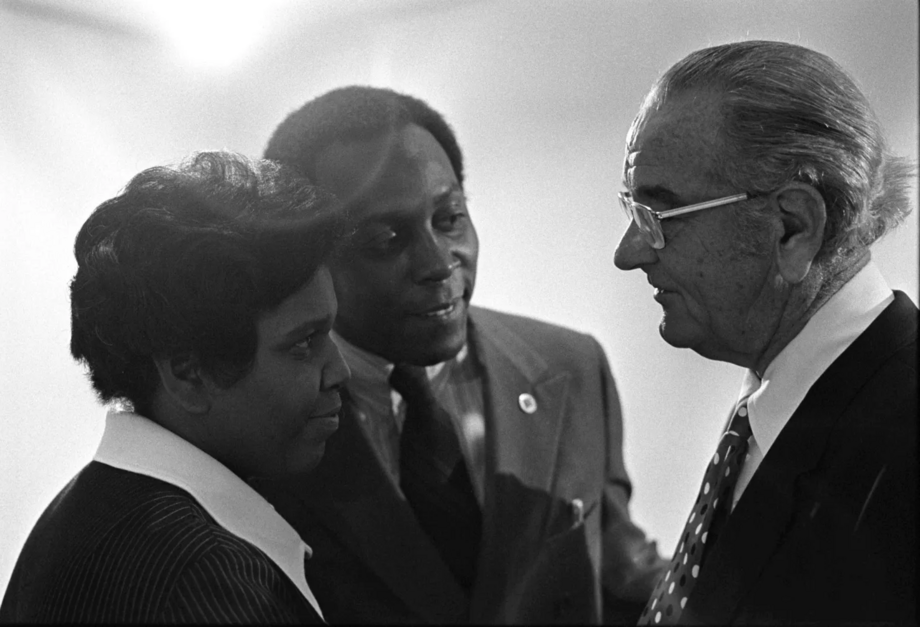

Barbara Jordan with Vernon Jordan and President Lyndon P. Johnson

Barbara Jordan

Born in Houston in 1936, Jordan overcame segregation and poverty to become the third Black attorney to practice law in Texas. Shortly afterward, she became involved in politics, running multiple campaigns for the Texas legislature. On her third try, she became the first Black woman elected as a Texas state senator and the first Black person since 1883 to serve in the Texas Senate.

In 1973, she successfully ran for US Congress and, from there, was placed on the Judiciary Committee. Around the same time, she began experiencing fatigue and a tingling sensation in her toes — symptoms that worsened until several tests, a spinal tap, and a heat bath confirmed that Jordan had multiple sclerosis.

Despite the hardship of her condition, Jordan remained dedicated to her work in Congress. Famously, she gave the opening statement during the Judiciary Committee’s first public hearing on Watergate.

She also made a name for herself as a staunch supporter of voting rights. She advocated for the expansion of the Voting Rights Act to mandate bilingual election processes; when President Gerald Ford signed the related amendments, Jordan stood beside him.

Jordan also supported the Equal Rights Amendment and other bills and resolutions dedicated to improving the lives of historically disenfranchised people.

“One thing is clear to me: We, as human beings, must be willing to accept people who are different from ourselves.”

Disability, Ableism, and Voting Rights Today

Voters with disabilities still face many barriers to casting their ballots.

In 2020, more than 11% of voters with disabilities faced difficulties casting their ballot despite increased access to mail-in ballots because of COVID-19.

The post-2020 surge of anti-voter legislation has only worsened this issue. From limited access to absentee ballots to the criminalization of voter assistance, several states have passed laws that create undue burdens on disabled people.

Yet some federal laws, like the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Voting Rights Act, are still in place to protect voters with disabilities. These laws require that election workers:

-

Make polling places fully accessible;

-

Allow voters with disabilities to receive in-person help at the polls; and

-

Make other reasonable accommodations if possible.

What Can You Do to Fight Ableism in Voting?

There are things you can do to promote accessibility and fight ableism at the polls:

-

It’s important to know your rights as a voter, whether you have a disability or you want to support other voters in the disabled community. Learn more about those rights.

-

If you’re a disabled voter and you’re facing challenges casting your vote, you can call the nonpartisan Election Protection Hotline at 1-866-OUR-VOTE.

-

Get the word out and promote Disability Voting Rights Week! Learn more, become a partner, and find a social toolkit here!

-

Support voters at the polls by becoming a poll worker.

-

Get involved in your community by joining your local League and engaging in their efforts to create more accessible voter tools and practices.

The Latest from the League

Today the League of Women Voters of Mississippi, Disability Rights Mississippi, and three Mississippi voters filed a federal lawsuit challenging SB 2358, newly passed legislation that significantly diminishes access to the ballot for Mississippians with disabilities. The plaintiffs are represented by Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), Mississippi Center for Justice, American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), ACLU-MS and Disability Rights Mississippi (DRMS).

The League signed onto a letter to US House leadership urging them to oppose the ADA Compliance for Customer Entry to Stores and Services (ACCESS) Act.

LWVUS joined other organizations urging committee members to support the restoration of the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund (BLDTF).

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate to support our work

to empower voters and defend democracy.