Understanding the Supreme Court's Gun Control Decision in NYSRPA v. Bruen

On June 23, the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its decision in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, overturning a New York gun safety law. The Court ruled that New York’s law requiring a license to carry concealed weapons in public places is unconstitutional.

Notably, the overturned law didn't exist in isolation; it was similar to laws in seven other states, the combined populations of which account for over a quarter of the people in the United States. The Bruen decision threatens those laws — in fact, Maryland suspended a similar law on July 8, just two weeks after the decision.

Two days after SCOTUS's ruling, President Biden signed bipartisan gun safety legislation, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, into law.

The Legal Question in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen

Bruen is the first major Second Amendment decision from the Supreme Court since District of Columbia v. Heller and McDonald v. Chicago, which enshrined the right to have a handgun for self-defense in the home. In Heller, the Court specified that some gun regulations were permissible, including bans on weapons in what the Court termed “sensitive places” like schools and churches.

The Supreme Court held oral arguments for Bruen in November 2021, with plaintiffs challenging the 100-year-old New York state handgun licensing law requiring individuals to show proper cause before they can be licensed to carry a concealed weapon in public. Plaintiffs argued that the law violates the Second Amendment. Defending the handgun licensing law, New York argued that the right to carry a weapon for self-defense outside the home is not absolute.

For more background on the law in question and the arguments on either side, read this LWV blog post.

The League's Involvement in the Gun Control Case

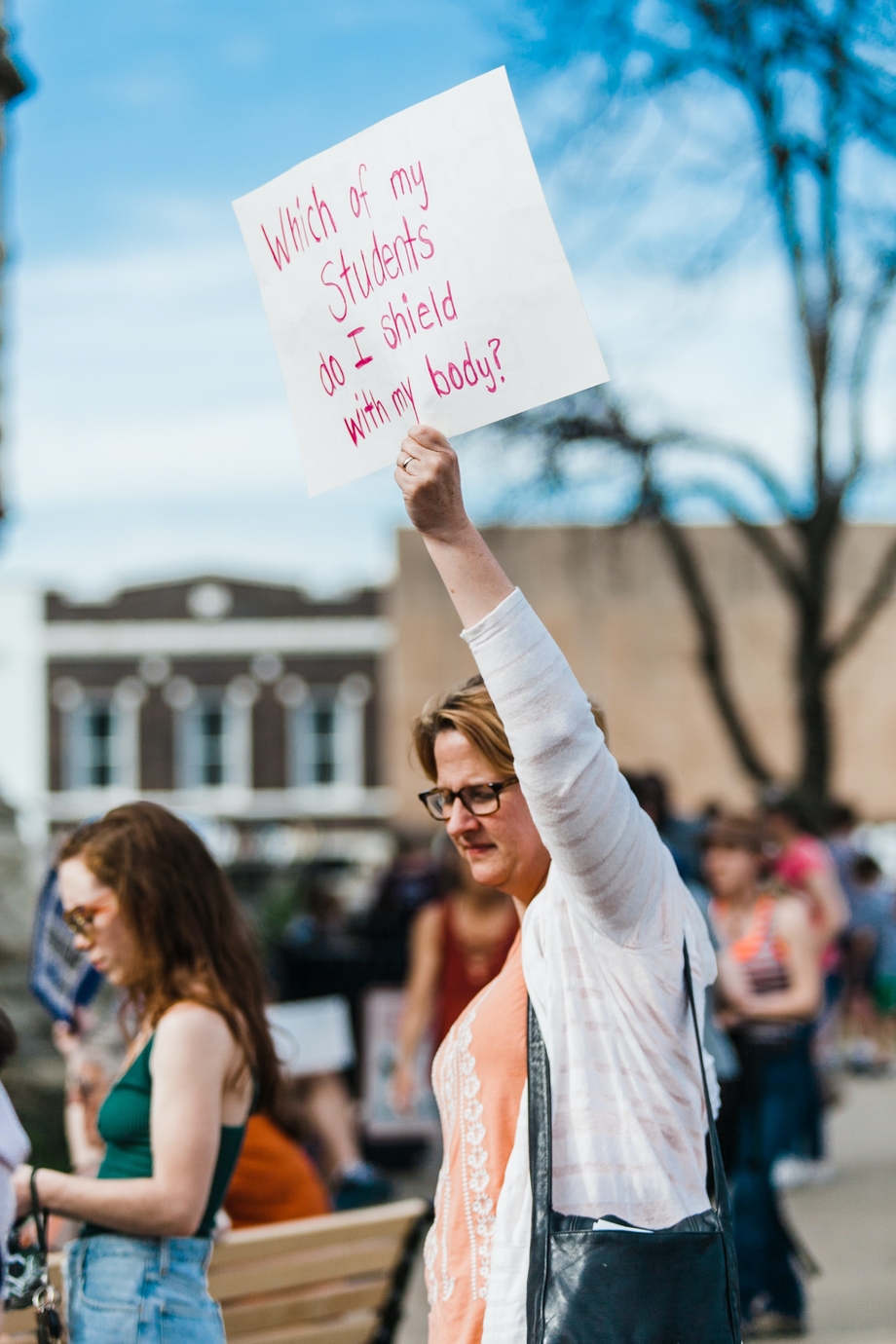

The League of Women Voters of the United States, along with the Leagues of Women Voters of New York and Florida, filed an amicus brief in Bruen. The brief highlighted polling places, which often include schools, churches, and government buildings, as “sensitive places” where firearm restrictions are necessary. As the amicus brief said, “the right to vote is meaningless without the right to vote safely.”

All stages of the democratic process, from protests before elections to casting one's ballot and counting votes, should be free from threats of violence and intimidation. The presence of firearms in any of these spaces is an inherent threat to public safety, especially considering our country's history of violent voter suppression against communities of color.

The Court's Ruling in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen

The Court ruled New York’s concealed carry law unconstitutional, extending the right to own a gun for self-defense in the home (as enshrined in Heller) to exist outside the home as well. Justice Clarence Thomas, writing for a majority of the Court, expressed concerns about what he saw as the subjective role of New York state officials in deciding whether someone applying for a concealed carry license has met the state’s requirements.

The Court distinguished New York’s law from other gun safety regulations, including requirements like the background checks in the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which are ostensibly more clearly defined. Now, other courts and legislatures must confront the question of what exactly constitutes too much discretion.

How Bruen Changes the Second Amendment Test for Gun Safety

Bruen altered the well-established test for evaluating gun safety laws, putting similar laws at risk in multiple states.

After Heller, most gun laws were upheld based on a two-part test asking:

- Whether the regulated conduct was protected by the Second Amendment, and

- If it was, whether the state’s reasons for enacting the law outweighed the burden created by the restriction.

As any constitutional lawyer will note, this type of test balancing a state’s interest with the restrictions imposed is commonplace in constitutional challenges to state laws.

Yet Bruen held that this test stretches the bounds of Heller because it gives too much discretion to state officials. After Bruen, the constitutionality of gun laws will be based on whether the plain text of the Second Amendment protects the activities the laws are regulating. If it does, then “the government must affirmatively prove that its firearms regulation is part of the historical tradition” to set boundaries on gun use.

This test seemingly only applies to the actual regulation itself, while not considering that the weapons being regulated have evolved from muskets to semi-automatic weapons since the days of the historical backdrop the Court uses in its analysis. Under this reasoning, the guns being regulated continue to evolve, but the regulations on those guns cannot.

This new test encroaches on the duties of state legislatures (not to mention Congress). Instead of allowing the legislative process to unfold, with elected lawmakers looking at on-the-ground realities and deciding the best ways to balance rights and restrictions, the Court said the balance has already been “struck by the traditions of the American people.” But it’s worth asking, what traditions? Traditions made by whom? And who struck the balance between Second Amendment rights and firearm restrictions? Who was, as they say, in the room where it happened?

The Silver Lining: Potential Protections for Voting Spaces

Amid the threats to gun safety, there is a silver lining. In its ruling, the Court affirmed Heller’s doctrine of “sensitive places,” and specified that polling places fit in that category. Each of the justices agreed that it is “settled” that there are “‘sensitive places’ where carrying guns could be prohibited consistent with the Second Amendment.”

In addition to polling places, the Court specifically named legislative bodies and courthouses. But the Court did not define sensitive places or address other places of mass congregation, such as protests and public transportation. Future lawsuits will likely have to find similarities between modern prohibitions and historically regulated “sensitive spaces” to determine whether contemporary gun laws are constitutional.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh, in a concurrence joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, noted that the Second Amendment still allows various gun safety regulations, affirming a central holding of Heller. They said states still may limit guns so long as they employ objective tests. Justice Kavanaugh listed a few presumptively acceptable regulations, including background checks. This concurrence will be key as Second Amendment litigation moves through lower courts, because either Justice Kavanaugh or Chief Justice Roberts will likely be needed to form any future Supreme Court majorities.

The Dissenting Opinion

Justice Stephen Breyer’s dissent was joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor and focused on the sobering reality of gun deaths in the United States.

The dissent emphasized that “the consequences of gun violence are borne disproportionately by communities of color, and Black communities in particular,” and noted the 277 mass shootings that had occurred this year as of the opinion’s release. In his concurrence, Justice Samuel Alito reminded Justice Breyer that the New York law in question did not prevent the recent mass shooting in Buffalo.

Justice Breyer registered three main criticisms of the majority’s ruling.

-

First, the Court made its decision based on insufficient evidence, deciding the case without any factual development. The Court never allowed the parties to engage in the legal process of discovering evidence, which would have allowed the Court to see the actual impact of the legislation. Instead, the majority made its ruling based only on the claims and responses made by the parties in the documents that initiated the lawsuit.

-

Breyer then critiqued the majority’s new test of Second Amendment history, taking issue with its “refus[al] to consider the government interests that justify a challenged gun regulation.” The dissenting justices believe balancing lawful uses of firearms against the potential dangers of that right is a job for the legislative branch, and the Second Amendment should not “prevent[] democratically elected officials from enacting laws to address the serious problem of gun violence.”

-

Finally, the dissent disputed Thomas’s interpretation of the history that the majority found to be so conclusive, addressing it point by point. The dissent noted that history is but one tool the Court possesses, and the majority relied on it excessively.

What Happens After Bruen?

In trying to make sense of the Court’s decisions in Bruen, what stands out is how the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority moved the constitutional goalposts. (The Court did the same in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the major abortion decision the Court handed down the day after Bruen.)

Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s concurrence noted that the Court’s decision in Bruen “should not be understood to endorse freewheeling reliance on historical practice from the mid-to-late 19th century to establish the original meaning of the Bill of Rights,” but the majority in Bruen did just that. The Court did not balance real-world interests with text and history, instead saying that we may only look to historical analogs.

Justice Breyer poignantly addressed this inconsistency in his dissent, writing:

"In each instance, the Court finds a reason to discount the historical evidence’s persuasive force. Some of the laws New York has identified are too old. But others are too recent. Still others did not last long enough. Some applied to too few people. Some were enacted for the wrong reasons. Some may have been based on a constitutional rationale that is now impossible to identify. Some arose in historically unique circumstances. And some are not sufficiently analogous to the licensing regime at issue here. But if the examples discussed above, taken together, do not show a tradition and history of regulation that supports the validity of New York’s law, what could? Sadly, I do not know the answer to that question. What is worse, the Court appears to have no answer either."

It is with this method and over the objections of the dissent that the Court invalidated New York’s law and altered the future of gun regulation in the United States.

The Latest from the League

WASHINGTON — Today League of Women Voters of the United States CEO Virginia Kase Solomón issued the following statement after President Biden signed the bipartisan gun safety legislation:

Today, the League of Women Voters of Texas issued the following statement after a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas

BUFFALO, NY & WASHINGTON — The League of Women Voters of Buffalo-Niagara, the League of Women Voters of New York State, and the League of Women Voters of the United States issued the following statement on the mass shooting in Buffalo, New York:

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate to support our work

to empower voters and defend democracy.