Why Elections Matter: Shelby County v. Holder’s Impact on the Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) was signed into law on August 6, 1965, by President Lyndon Johnson. The VRA outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, including poll taxes and literacy tests as prerequisites to voting. The Act also sought to remove other obstacles Black Americans experienced when attempting to vote, including harassment, intimidation, economic punishments, and physical violence.

Upon its passage, the VRA had an immediate impact. By the end of 1965, a quarter of a million new Black voters were registered. By the end of 1966, only four out of 13 southern states had fewer than 50 percent of their Black American population registered to vote. Because of this progress, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was readopted and strengthened in 1970, 1975, and 1982.

Arguably, the VRA has become the most instrumental mediator in the relationship between federal and state governments around voting access since the Reconstruction period. But even as the government sought to enfranchise Black Americans through the VRA, states immediately challenged the new law in the courts. And while several VRA challenges emerged, very few cases had as negative an impact as Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which erased fundamental protections against racial discrimination in voting by striking down Section 4 of the VRA.

Ten years later, the Shelby County challenge — what led to it and the impact of the decision — reinforces why elections remain so important and why protecting access to the ballot is even more critical now.

The City Council Election That Fueled a Federal VRA Challenge

The Shelby County v. Holder case arose from turmoil over a contentious local election. Ernest Montgomery, a Black American, was elected to the city council in Calera, Alabama, in 2004. Yet, while he was serving on the council in 2006, city officials facing a population boom redrew his district map to benefit a white candidate. When officials redrew the map, the minority representation in Montgomery's district decreased from 67% Black American to approximately 28%. Not only did the redrawing of the map reduce minority representation by nearly 40%, but it also did so illegally because the city council failed to get approval in violation of the preclearance requirements of the VRA.

Following the illegal map drawing, Montgomery, the city’s only Black councilman, lost his 2008 reelection by just two votes. Montgomery and others were confident that his loss was due to the district's reduced population of voters of color.

Support our work to end voter discrimination

The botched election made news, and questions arose about whether the Calera City Council's election was illegal. The Department of Justice sued the City of Calera under Section 5 of the VRA, and the city was required to draw a new, nondiscriminatory redistricting plan and hold another election. When the dispute was resolved, a new election date was set, and Black voters selected their candidate: Mr. Montgomery regained his city council seat. Without Section 5, this reversal would not have happened.

Alabama's Challenge to the Voting Rights Act of 1965

Following Councilman Montgomery’s re-election, local election officials began to question the legitimacy of the VRA and whether sections of it should still apply to Alabama. And in 2013, the US Supreme Court agreed to look at a new case out of Alabama challenging the constitutionality of two of the VRA's provisions, just as the 50th anniversary of the Act approached.

The first provision the City of Shelby wanted to examine was Section 5, which required certain states with a history of discrimination to gain federal approval before changing their voting laws or practices. Federal oversight meant that the US Attorney General, or a court of three judges in Washington, DC, reviewed possible amendments to state electoral laws before localities could pass them. The significance of section 5 was that it put the responsibility on local and state jurisdictions to clear electoral changes with the federal government before enacting the change.

The second provision called into question was Section 4, which helped the federal government examine those states with a history of discrimination. Any changes these states made to their voting laws required preclearance from the federal government. Specifically, preclearance was required in jurisdictions with less than 50% voter turnout and those with a history of electoral laws that allowed the use of tests to determine voter eligibility.

Initially, the VRA expired after five years, but Congress amended and reauthorized it several times due to the continued prevalence of racial discrimination nationwide. As a result, Congress reauthorized the Act in 1975, which updated Section 4 with a requirement to review the Act after 25 years. The VRA was updated again in 1982 and 2006.

Shelby County v. Holder and Alabama’s History of Racial Discrimination

There were two key questions before the US Supreme Court in the Shelby County case:

-

Can the federal government use formulas to determine which states require oversight if they want to change electoral laws?

-

How often must those formulas be updated to remain constitutional?

Under the formula in the VRA, Alabama had to get approval for voting changes because the federal government determined that the state had a history of racial discrimination in voting.

Those familiar with the fight for voting rights in Alabama know that the state was home to one of the most infamous and violent protests in American history — Bloody Sunday. On a Sunday in 1965, people peacefully protesting the murder of voting-rights activists in Mississippi were attacked by white state troopers with billy clubs and tear gas in Selma, Alabama.

The late John R. Lewis was an organizer of the march, and he was later elected to Congress. Lewis was vocal about his horrific experience that day. Recounting his experience to CNN in 2015, he said, "I went down on my knees. My legs went out from under me. I thought I was going to die."

Bloody Sunday persuaded President Johnson and Congress to enact meaningful and effective national voting rights legislation. The combination of public revulsion to the violence and Johnson's political skills moved Congress to pass the VRA in the first place.

Despite Alabama's history of racism, in Shelby County v. Holder, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the majority opinion in a 5 – 4 decision invalidating important parts of the Voting Rights Act. Justice Roberts wrote that certain sections of the VRA were invalid because of Congress' decision to reuse language and formulas that have existed since 1975. Justice Roberts went on to write that the VRA gave the federal government unprecedented power over state legislatures with a specific goal — preventing state and local governments from using voting laws to discriminate. He claimed that the law had accomplished its purpose and successfully decreased voter discrimination. He reprimanded Congress, saying, “Congress should have acknowledged the bill's impact and slowly altered it to account for that change.”

However, all the justices did not agree. Justice Ruth Ginsburg authored one of the most well-known dissenting opinions in US Supreme Court history when she wrote:

“[V]oting discrimination still exists; no one doubts that. But the Court today terminates the remedy that proved to be best suited to block that discrimination. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has worked to combat voting discrimination, whereas other remedies have been tried and failed. Particularly effective is the VRA's requirement of federal preclearance for all changes to voting laws in the country's regions with the most aggravated records of rank discrimination against minority voting rights."

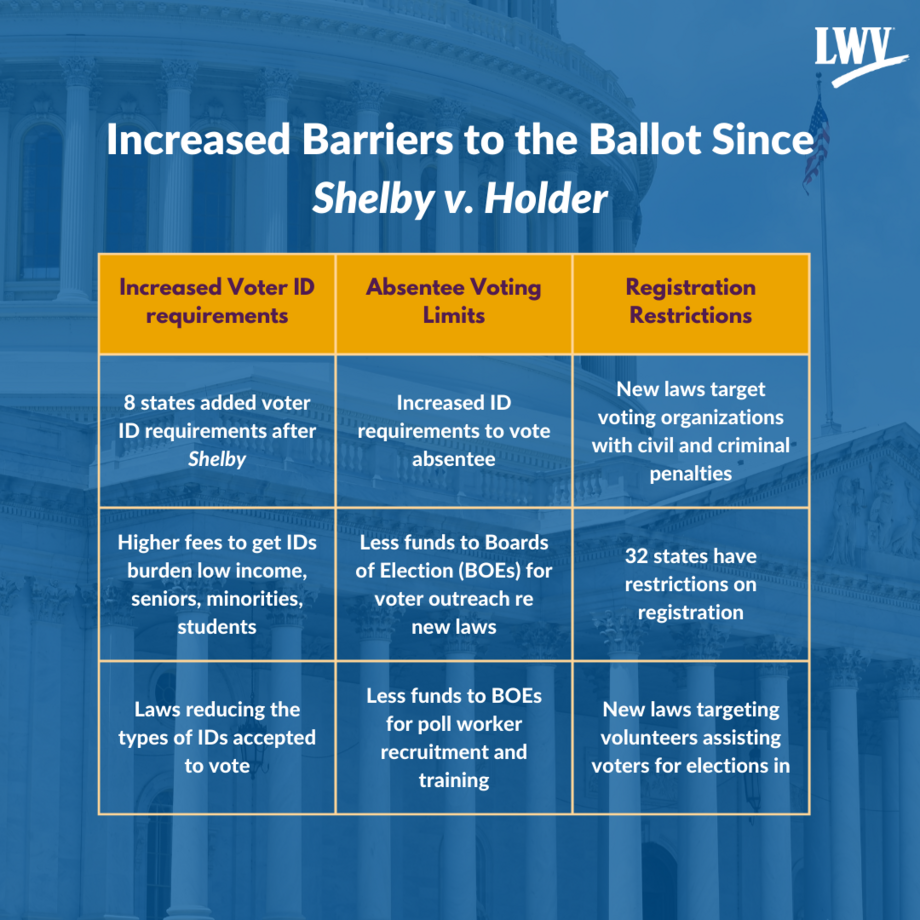

Detrimental Impacts post-Shelby County v. Holder: Voter ID, Absentee Voting, and Voter Registration

Following the Shelby decision in 2013, massive education campaigns led by voting rights organizations emerged nationwide. The education campaigns aimed to inform voters of the impact Shelby County would have in the jurisdictions previously covered by the Voting Rights Act. Since the gutting of Sections 4 and 5, their states have enacted more limitations on voting access through strict voter ID requirements, severe limitations on absentee voting availability, and restrictions on voter registration processes and practices. The chart below shows the increased barriers to the ballot since Shelby County v Holder:

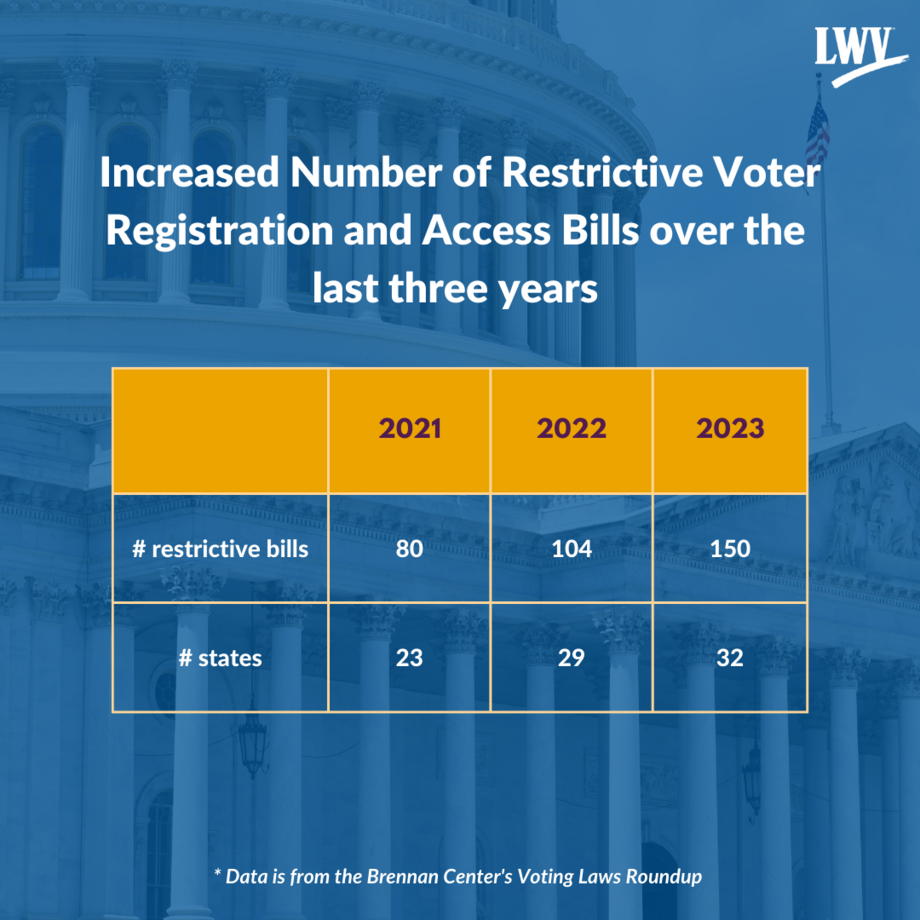

Following the 2020 election, state legislatures began passing more laws restricting voter registration activities and targeting third-party voter registration organizations like the League of Women Voters. Each year, the number of restrictive voting bills introduced in states continues to grow, showing a vested effort to disenfranchise millions of voters nationwide.

The chart below uses data from the Brennan Center to show the increased number of restrictive voter registration and access bills over the last three years:

The threat to voters could not be clearer. We must recognize the impact of Shelby County v. Holder for what it was: an intentional act to target and exclude some voters from the electoral process. And without reforms to restore voters' access to the ballot through relaxing or eliminating strict voter ID requirements, increasing absentee ballot availability, and making it easier for individuals to register to vote with effective and nondiscriminatory methods, organizations like the League will have to stay vigilant in educating communities about the election laws in their state and working overtime to encourage voters to participate in elections and to feel confident that they can cast their vote safely.

Five Actions You Can Take Now

-

Register to vote and check your registration status. VOTE411.org is a bilingual one-stop shop that anyone can use to check their voter registration, find out the upcoming elections in their area, and learn where and how to cast their ballot.

-

Ensure that your family and friends know where and how to cast their ballot during early voting, if applicable, and on Election Day. Tell them about VOTE411.org.

-

Join your local League to get informed and stay engaged around issues that impact your community. Participate in letter-writing campaigns to your state legislature. Tell them why laws that restrict access to the ballot are unacceptable.

-

Join League in Action, the app you can use to find out advocacy opportunities in your community and connect with local League members and neighbors.

-

Let your representatives know they must act to empower voters! Find pro-democracy messages to send to your reps.

The Latest from the League

Voter ID laws have long been debated in the United States. While supporters argue that voter photo ID laws are necessary to prevent voter fraud and ensure the integrity of elections, reality tells a different story. Not only do these measures disproportionately impact Black, Native, elderly, and student voters, but they also fail to effectively address any real issues related to election integrity.

The League’s history of breaking down barriers to voting is perhaps best exemplified by its contribution to the passage of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) in 1993. This legislation makes it easier for all Americans to register to vote and maintain their registration.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) was signed into law on August 6, 1965, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. It was a proud day in American history. But the history to get to this point was stormy and full of thorns. And today, we have neither tamed the storm nor nipped the thorns still present as we work towards the American dream of life, liberty, and justice for all.

Sign Up For Email

Keep up with the League. Receive emails to your inbox!

Donate to support our work

to empower voters and defend democracy.